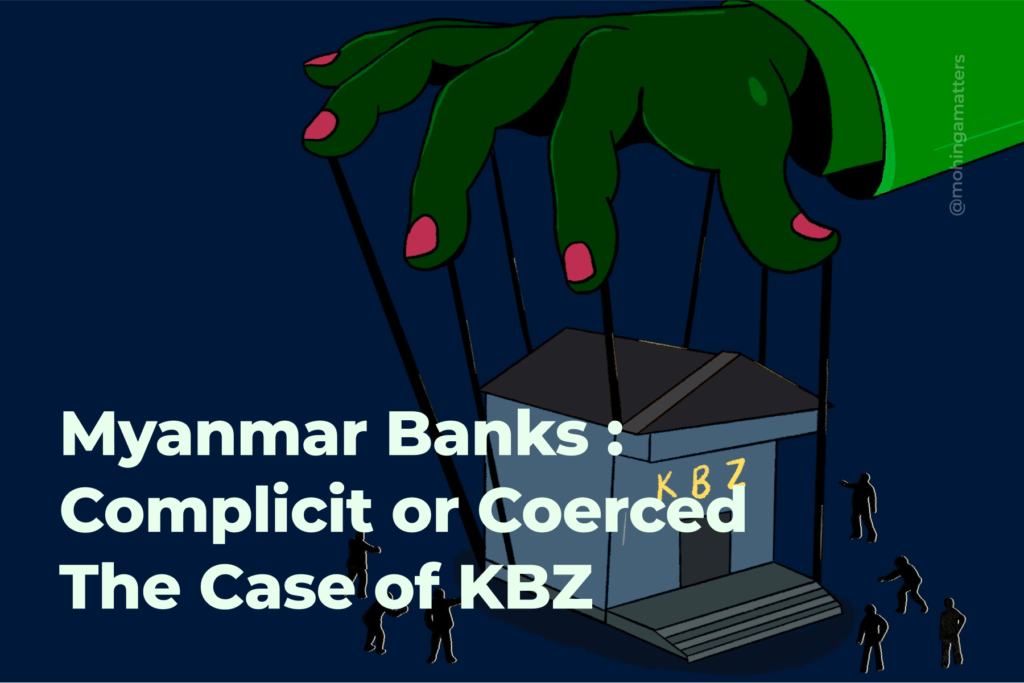

In nearly all dictatorships, the financial system becomes a tool of repression. The events following Myanmar’s 2021 military coup have shaken not only the political landscape but also the nation’s financial institutions, with KBZ Bank, the country’s largest private bank, caught in the crossfire. On September 16, Kanbawza Bank (KBZ) announced a donation of 10 billion Myanmar Kyats for victims of the Typhoon Yagi-related floods. However, just days later, reports surfaced that hundreds of KBZ’s digital wallet (Kpay) accounts had been frozen and suspended. Ironically, many of these accounts were engaged in the same charitable activities that KBZ had publicly supported. Users had included notes on their transactions indicating that the funds were donations for flood victims. This led to widespread confusion and disbelief among the public, especially as these suspensions were carried out under the pretext of suspected links to money laundering activities. Those attempting to help the flood victims were left baffled by the bank’s contradictory actions. This contrast between the bank’s charitable donation and its crackdown on public efforts reflects a broader tension within authoritarian systems, where public goodwill can be suppressed under questionable pretenses.

This is not the first time the bank has come under scrutiny. KBZ has been complying with Myanmar’s junta in freezing accounts of those who are suspected to link to pro-democracy movements as Myanmar’s Central Bank, now controlled by the military junta, continues to issue directives to freeze the accounts. Although other banks such as CB bank and AYA bank are equally complicit in junta’s crimes, KBZ came top since its mobile pay is the most popular with six million Myanmar’s users across the country. Questions are growing about the role and accountability of these corporate banks such as KBZ under an authoritarian regime. What responsibility does KBZ Bank hold for its complicity? And more importantly, will the bank ever pay back what it owes to the people?

Since the coup, KBZ Bank and its mobile banking platform, KBZPay, have been accused of enabling the military regime by freezing accounts tied to the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM) and other opposition activities. Reports indicate that many of these account freezes have targeted individuals and organizations providing financial support to the National Unity Government (NUG), the political body representing opposition to the junta. Many users responded to KBZ’s action by giving negative reviews on the app store and calling for a boycott. This alignment with the junta’s directives has not only undermined the bank’s credibility but also made KBZ a key player in Myanmar’s financial repression. KBZ has complied with military orders to restrict funds under the guise of preventing illegal activities. However, evidence suggests that the regime is using banking institutions as tools to cripple pro-democracy forces. The bank has followed these orders, although there are questions regarding how much of its cooperation is voluntary and how much stems from duress under military threats.

One of the major questions facing KBZ Bank is whether it will be held financially accountable for freezing the accounts of Myanmar’s citizens. Thousands of individuals and businesses have lost access to their funds, severely damaging both livelihoods and public trust in the banking sector. As the military continues to clamp down on dissent, these measures are likely to persist, making the possibility of financial restitution uncertain. If Myanmar undergoes a democratic transition in the future, a new government could demand that KBZ and other banks pay reparations to those whose funds were wrongfully frozen. However, such accountability will depend on the legal and political framework of the new administration. If the new government is weak or lacks a mandate to pursue reparations, the financial institutions may escape legal responsibility.

In countries under military regimes or authoritarian governments, financial institutions often avoid accountability for their complicity, sometimes citing coercion or external pressures. For example, during Robert Mugabe’s rule in Zimbabwe, financial institutions largely avoided penalties for collaborating with the regime. They often used the defense that they were operating under governmental coercion, which created a protective layer against direct consequences for supporting repressive policies. The economic crisis in Zimbabwe, exacerbated by sanctions, often led banks to align with Mugabe’s government for survival, even as their actions contributed to human rights violations and economic instability. Although many banks and companies were listed under sanctions, most evaded direct repercussions by blaming external factors or poor governance rather than accepting responsibility for their complicity in the regime’s actions.Comparatively, in Myanmar, corporate banks like KBZ and CB Bank have faced similar challenges under the junta’s directives. These institutions have frozen accounts under the guise of preventing money laundering, while simultaneously making significant donations to humanitarian causes, as seen with KBZ’s contribution to flood relief. The tension between publicized charitable efforts and compliance with authoritarian measures mirrors cases in other countries, where banks maintain their operations by walking a fine line between supporting repressive regimes and engaging in philanthropic activities to preserve public image. The question remains whether these banks will be held accountable or whether post-junta, they will face any penalties for their actions during the military’s reign.